BLOG

Soulection: The Once and Future of R & B

When Los Angeles-based Soulection released “Love Is King,” a tribute mix to Sade, the response was both immediate and noteworthy. The collection of mixes, crafted by label beatmakers, gave a whole new soundscape to familiar and beloved songs by the band and placed it’s eponymous lead singer in a new context – celebrated and adorned. Almost like a very elaborate “thank you” for … existing.

When Los Angeles-based Soulection released “Love Is King,” a tribute mix to Sade, the response was both immediate and noteworthy. The collection of mixes, crafted by label beatmakers, gave a whole new soundscape to familiar and beloved songs by the band and placed it’s eponymous lead singer in a new context – celebrated and adorned. Almost like a very elaborate “thank you” for … existing.

Before we continue, I must admit, I am not a fan of sub-genre naming. Sometimes it makes sense, but like “neo-soul” - that was kind of stupid – it is just soul, folks. I don’t consider “Future R & B” a genre as much as it is an idea. It exists firmly in the now, while reaching back to the past.

This isn’t a new concept, of course – Funk (an appropriate sub-genre, mind you) is a precursor to this idea. Take pieces of musical experiences, put them in the wash then rinse and spin it through your personal filter.

In modern R & B, the first glimmers of what the “future” sound could be appeared in 1997 – “One In A Million.” The album was full of masterfully crafted electronic, bass heavy, rhythms with a sweet, high-pitched voice on top (courtesy of Detroit daughter, Aaliyah). The title track encapsulates the idea perfectly. It’s a classic R & B song, one in which you can imagine a standard jazz version existing, for instance. Rooted in R & B traditions, but placed firmly in the year it was created. Both a logical and illogical blending of hip hop, soul, jazz and funk.

It’s in this context that the sounds of many of the beatmakers of Soulection take shape. It’s clear that they grew up idolizing the Timabalands and The-Dreams of the world, but have the youth, talent and access to the tools to create a new sound.

Interestingly, this sound has the potential to do something unexpected. It teaches history.

It’s fitting that the label used Sade to celebrate having 200K followers. We only get a record from the band once a decade, at this point – i.e. twice a generation. That means that a listener’s connection to this pivotal act is diminished, because there’s no new material.

By using current beat making techniques, and layering in classics, the Soulection sound is breathing new life into music that changed the time it was created in. Now, those past songs have the opportunity to change the future.

Wear your shades - the future's bright!

To Pimp A Culture – From "Compton" To Here

In 1991, when the MP3 audio format was just becoming more than a twinkle in the eyes of developers, rap music was on the verge of making a sharp left turn. Few of us knew how drastic the change would be. It certainly paralleled the tenor of the US at that time.

In 1991, when the MP3 audio format was just becoming more than a twinkle in the eyes of developers, rap music was on the verge of making a sharp left turn. Few of us knew how drastic the change would be. It certainly paralleled the tenor of the US at that time.

Remember George H.W. Bush, Jack Kevorkian, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, “Peace In The Middle East,” and Rodney King? Yes, the world was very different, then.

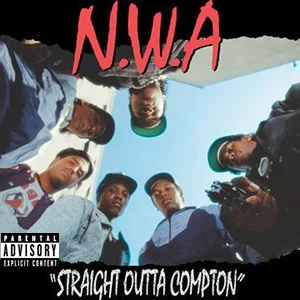

For a brief moment, let’s stay with Mr. King. Before the Los Angeles Rodney King police brutality video and subsequent riot after officers were acquitted, New York City was the center of the Hip Hop universe. A few short years before that, though (in 1988), an album had emerged – “Straight Outta Compton.”

The album cover was immediately striking. Why? The gun. Yes, there had been guns on Rap album covers before, but this gun – this gun was pointed at me (… and you) while we were lying down looking up at it. This is not a position anyone wanted to be in, of course, but it was happening. “Straight Outta Compton,” while profane, was rather pro-black militant, however. The album opened with the Dr. Dre exclaiming “you’re about to witness the strength of street knowledge.” It was on! The spotlight on California was being turned up and rap music was publically growing up.

The album cover for “Straight Outta Compton” has been lauded as one of the best album covers – ever. It communicated what had been simmering in the consciousness of Los Angeles for many years , communicated what was happening at the time and it foretold the direction that the music (and the world, frankly) would take. Thanks to photographer Eric Poppleton for capturing this vivid image.

By 1991, the West Coast – Los Angeles, in particular – had made significant inroads into the Rap music landscape commercially, and in a short year later would take over completely with the release of “The Chronic.”

Fast forward 24 years.

The MP3 has not only been birthed, but is now all grown up, and is a standard for how music is not only transferred digitally, but consumed by the music buying public. Record stores – virtually closed or hanging on by a thread. Cassettes – nostalgic. CDs – passé. Vinyl – what is that?

I often remark how I miss having physical album art, because I learned a lot about the background of the music having it, and I also had something cool to put on the wall. Album art, however, is not prevalent, because music isn’t consumed as a physical product anymore.

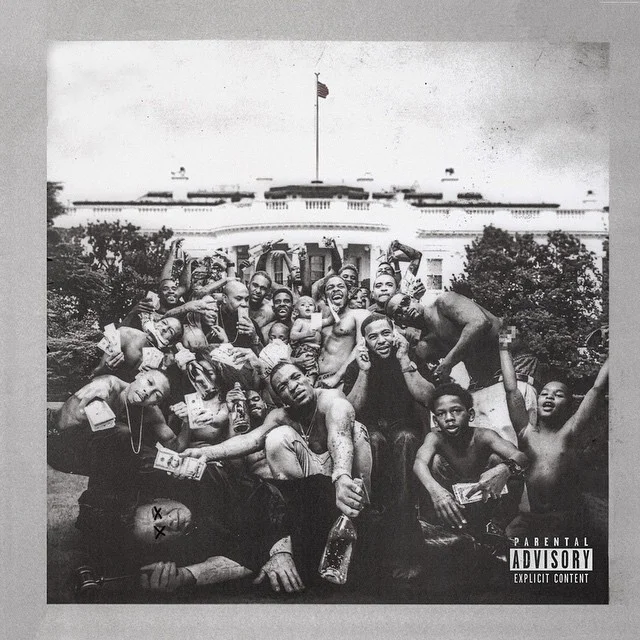

It’s in this context that the excellent album cover for Kendrick Lamar’s “To Pimp A Butterfly” emerges. Now, I’ll admit, the fact that both of these artists are from Compton didn’t dawn on me when I made the decision to talk about these two covers, but I do find the fact interesting.

While in 1988, “Straight Outta Compton,” was bold and brash, in 2015 we are virtually desensitized to such content. So, I’m going to make a statement now that you may disagree with.

If we took the album cover for “To Pimp A Butterfly” and placed it in 1988, it would be even more controversial than the “Straight Outta Compton” artwork.

Why do I say that?

In 1988 the country was still very conservative and rap music, as a phenomenon, was still young and evolving. An album cover depicting overzealous, shirtless black men holding stacks of money, champagne and children while standing on the white house lawn and crushing (to death) “the law” would have not only outraged White America, but would have infuriated Black America. What’s even more startling is that the image that is depicted, while not actually being the norm today, is the most common depiction of black men that we see.

If we piece together the time between “Straight Outta Compton” and “To Pimp A Butterfly” the arrival at this cover makes perfect sense. It’s today. It’s now. It’s post-crack. It’s post-Katrina. It’s post-Iraq. It’s post-Tech boom. This is how black men are seen by the world – uncontrollable, sexualized, not law-abiding and careless.

Admired.

Butterflies.

Hated.

Pimps.

Album cover art isn’t insignificant. I’d argue the packaging is as important as the content. It communicates the artist’s vision, and it also serves as a slice of life for where we are as a society at that moment.

From “To Pimp A Butterfly” where do we go from here?

"Blurred" Ruling - How Inspiration Became Infringement

First, a little backstory ...

When I first heard "Blurred Lines," I was in a club. I had been dancing, when I suddenly stopped mid-dance, turned to Brody and exclaimed "what the hell is this?" He then informed me that it was the new Robin Thicke song. I remember curiously listening, deciding that I didn't really dig it, that they channeled Marvin almost to the letter with the groove, but not quite.

Cover Art: "Live At The London Palladium" by Marvin Gaye (Tamla Records, 1977)

First, a little backstory ...

When I first heard "Blurred Lines," I was in a club. I had been dancing, when I suddenly stopped mid-dance, turned to Brody and exclaimed "what the hell is this?" He then informed me that it was the new Robin Thicke song. I remember curiously listening, decided that I didn't really dig it, and that they channeled Marvin almost to the letter with the groove, but not quite.

Fast forward ...

"Blurred Lines" is literally everywhere, undoubtedly making tons of money, and still heavily steeped in a very distinct groove - (Pause). "Got To Give It Up" is a very unique sounding song from the head of Marvin himself, but influenced by elements of funk, jazz and doo-wop. It uses a recognizable percussive arrangement, that, if imitated, would instantly remind you where it came from. Sidebar: It unseated "Dreams" as the Hot 100 #1 song in 1977. "DREAMS" - yes, by Fleetwood Mac - that amazing song.

I was shocked when I learned that the writers had launched a preemptive lawsuit against the Gaye family to prove the song's originality. I was shocked not because I think they stole "Got To Give It Up" - they clearly didn't - but because "Blurred Lines" was a heavily influenced song. So much so I thought that Gaye should have been credited in the first place. Remember, "Got To Give It Up" is really distinct.

This is where the traditional rules of how to think about copyright infringement get a little muddy. There's always been the thinking that "you can't copyright a groove" in music. Generally, I think that's true, because everything is an influence on something. This case challenges that idea, because in some cases that sound, rhythm or combination is so distinct that it truly is intellectual property that may be, in fact, uniquely owned and can be challenged. I just can't think of a time when anyone has actually tried to challenge it before.

There are certain rhythm patterns that seem like they've always been in existence. Reggae music is a good example of this. Ask any person what reggae sounds like and they're guaranteed to give you the same guitar pattern. Which is based on the drum pattern, and is distinct to that genre of music. Infringement? Maybe 50 years ago yes, but now, I'd argue no. Who owns that rhythm pattern? It's public domain at this point, because it's on so many recordings.

I didn't think the Gaye family would win their lawsuit, based on the way these cases have been tried before, and it was clear it wasn't the same song. I was both excited and scared when they did win.

The sky isn't falling.

This doesn't mean that artists can't use influence to create anymore. It does mean that acknowledging that influence and how to proceed with it may be something to think about. (Do it after you're done as to not impede your creative process. Trying to not do MJ, while trying to be MJ-like is just too much thinking, ladies and gents.) Use your network to ask the questions if you need to. I would have advised the writers engage the Gaye estate for permission to credit Gaye and ensure royalties were paid. It was just the right thing to do in this case.

In closing, this is a good time to mention that this ruling does have implications in all areas of creative expression. Painters - watch out for using distinct strokes, color pallets and composition ideas. Choreographers - watch out for using certain movement combinations from key pieces. The line is a bit more blurred.

This note was inspired by this article. I did not copy, infringe, quote or interpolate it. :-) I think it's good reading though. http://www.vulture.com/2015/03/what-the-blurred-lines-ruling-means-for-music.html